Set Operations on Functions

Functions are sets, so we can try to combine them like we combine sets. That is, we can ask the following questions:

- Is the complement of a function necessarily a function?

- Is the intersection of two functions necessarily a function?

- Is the union of two functions necessarily a function?

- Is the set product of two functions necessarily a function?

Let's investigate the first three; the last one I'll leave for homework.

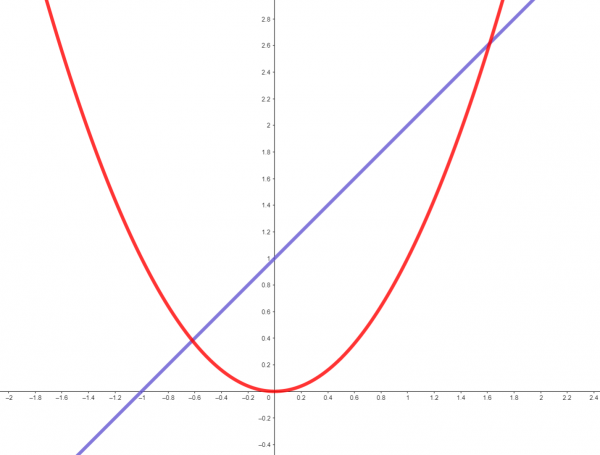

To start with, let's pick two functions and run with them. How about: ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

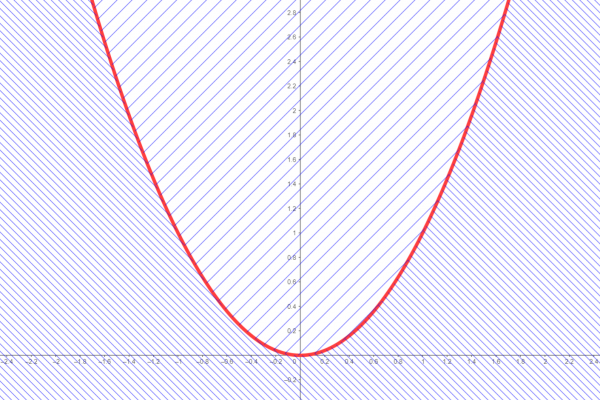

The complement of ![]() is

is ![]() , shown here in hatching:

, shown here in hatching: That's definitely not a function: it badly fails the vertical line test.

That's definitely not a function: it badly fails the vertical line test.

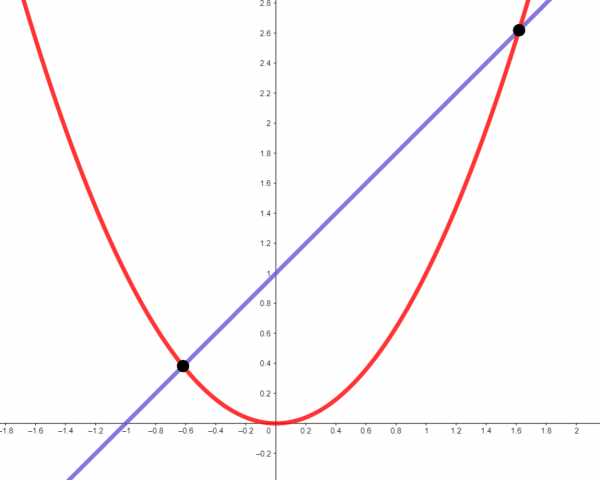

What about intersection?

The intersection is just two points; so ![]() is not a function from

is not a function from ![]() to

to ![]() . But

. But ![]() is a function from a smaller set.

is a function from a smaller set.

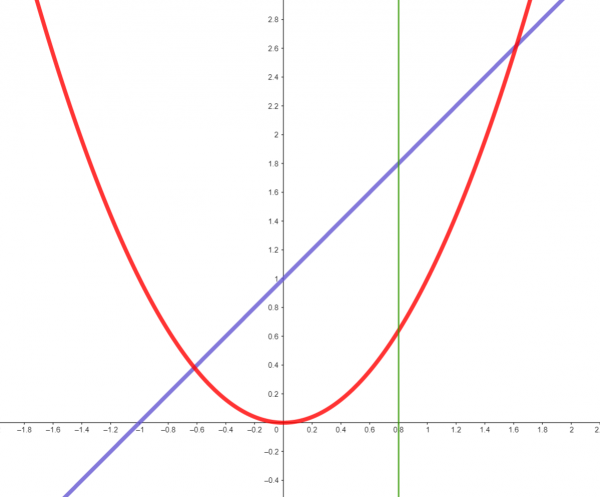

Let's look at ![]() :

:

It also fails the vertical line test. But:

The Pasting Lemma (in the category of sets). Let ![]() and

and ![]() be two functions. Then

be two functions. Then ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() .

.

Proof. This is a biconditional, so we have two directions:

(![]() ) Assume

) Assume ![]() . We need to show

. We need to show ![]() is a function; to do this, there are two clauses.

is a function; to do this, there are two clauses.

(clause 1: domain) Let ![]() . Then either

. Then either ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

If ![]() , then because

, then because ![]() ,

, ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() .

.

If ![]() , then because

, then because ![]() ,

, ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() .

.

In either case, there's an element of ![]() so that

so that ![]() . That's clause 1 of the definition of function.

. That's clause 1 of the definition of function.

(clause 2: unambiguousness) Let ![]() and

and ![]() be such that

be such that ![]() and

and ![]() . There are four cases:

. There are four cases:

If ![]() and

and ![]() , then the fact that

, then the fact that ![]() is a function implies

is a function implies ![]() .

.

If ![]() and

and ![]() , then the fact that

, then the fact that ![]() is a function implies

is a function implies ![]() .

.

If ![]() and

and ![]() , then we have

, then we have ![]() and

and ![]() , so

, so ![]() . But then

. But then ![]() . So

. So ![]() . So

. So ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is a function,

is a function, ![]() .

.

If ![]() and

and ![]() , then we have

, then we have ![]() and

and ![]() , so

, so ![]() . But then

. But then ![]() . So

. So ![]() . So

. So ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is a function,

is a function, ![]() .

.

In any of these four cases, ![]() , which is what we needed for clause 2 of the definition of function.

, which is what we needed for clause 2 of the definition of function.

(![]() ) In this direction, we need to show two functions are equal. So we should probably use the TAWFAE. I'll leave this direction to you.

) In this direction, we need to show two functions are equal. So we should probably use the TAWFAE. I'll leave this direction to you.

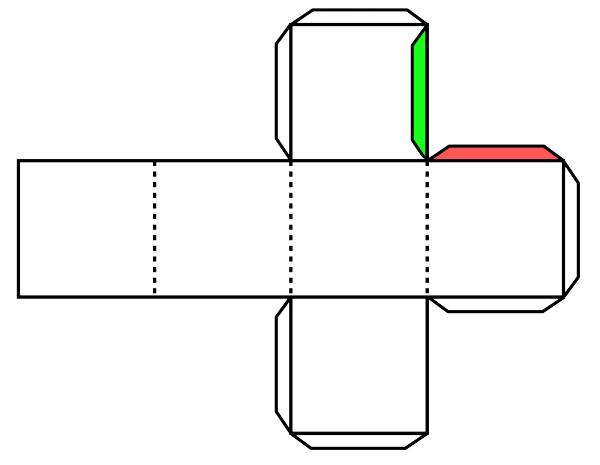

Why does this theorem bear such a silly name? Consider this diagram, which tells you how to build a cube from a piece of paper. In order to attach the sides, you have to paste the red tab to the back of one of the appropriate square (I've indicated where the red tab gets attached by coloring it green). We won't succeed in pasting unless the red tab and the green target match up.

That's what the condition ![]() ensures: that the functions

ensures: that the functions ![]() and

and ![]() agree on the overlap of their domains.

agree on the overlap of their domains.

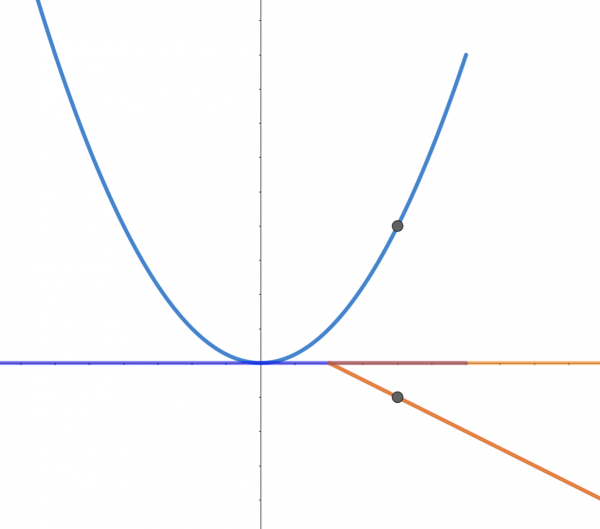

Again, an example from precalculus mathematics: when we define a function piecewise, like

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[h(x)=\begin{cases}x^2 & \text{ if } x\leq 3\\ -x+1&\text{ if } x>3\end{cases}\]](https://ma225.wordpress.ncsu.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-1c2e81bd5163209d38243890482fd9d5_l3.png)

we usually want to make sure that the two pieces have nonoverlapping domains. This corresponds, in the Theorem above, to the case that ![]() . If we weren't so careful, we might have a situation like this:

. If we weren't so careful, we might have a situation like this:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[h(x)=\begin{cases}x^2 & \text{ if } x\leq 3\\ -x+1&\text{ if } x>1\end{cases}\]](https://ma225.wordpress.ncsu.edu/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-337d5a18dbab3136329a91fe177c8d8c_l3.png)

where it's ambiguous what ![]() is:

is:

Composition of Functions

Because functions are relations, we can consider their composites. We have the following nice theorem:

The Composition of Functions Is a Function. If ![]() and

and ![]() , then

, then ![]() .

.

Proof. There are two things to show:

(clause 1: domain) Let ![]() . Then, because

. Then, because ![]() is a function,

is a function, ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() and

and ![]() is a function,

is a function, ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() .

. ![]() .

.

(clause 2: unambiguousness) Given ![]() so that

so that ![]() and

and ![]() . We need to show

. We need to show ![]() .

.

Since ![]() , there is some

, there is some ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() . We also have

. We also have ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Since ![]() is a function,

is a function, ![]() . So we have

. So we have ![]() . But since

. But since ![]() is a function,

is a function, ![]() and

and ![]() forces

forces ![]() .

. ![]() .

.

Important Formula. If ![]() and

and ![]() are functions, so that

are functions, so that ![]() is a function, then

is a function, then ![]() .

.

Proof. What does it mean for ![]() ? It means

? It means ![]() . But that means

. But that means ![]() and

and ![]() . So

. So ![]() and

and ![]() . By substituting, we obtain

. By substituting, we obtain ![]() .

. ![]()

This formula explains the "backwards" looking choice of how we write compositions: even though ![]() come first, we write

come first, we write ![]() . The only way out of this would be to switch our function notation to something like

. The only way out of this would be to switch our function notation to something like ![]() , so that the composite would be

, so that the composite would be ![]() . (Some people do this, and it has a name: reverse Polish notation. But most normal people don't do it.)

. (Some people do this, and it has a name: reverse Polish notation. But most normal people don't do it.)